BLOG – What We’ve Learnt From Delivering Youth Climate Action

This is a blog written by Groundwork Greater Manchester’s youth team with support from Dr Benjamin Bowman at Manchester Centre for Youth Studies and Manchester Metropolitan University, as well as young people living in Manchester.

It is part of a series of blogs discussing youth and climate action. You may also be interested in reading the other articles here:

- Inequality in climate action & considerations for the youth sector

- What does youth climate action look like?

- Top Tips for delivering youth climate action projects

Background

In 2020 Groundwork GM identified that there were a few challenges with how we, and the wider youth sector, were engaging young people about the topic of climate change.

Challenges included:

- The climate movement didn’t really reflect the young people we we’re working with and their interests: For a lot of the young people in the communities we’re working with, climate change isn’t on their agenda, and the communities are more concerned around other issues: poverty, pollution, knife crime or fuel poverty.

- Decisions around climate change were mostly made by a certain demographic: predominately privileged, white and middle-class. Examining the suggested actions on how people can contribute to tackling climate change, we learned that these are often top-down, individualistic and based on suggestions for substituting one consumption habit with another, more sustainable one.

Successfully youth work requires activities to be youth-led, so we needed to find a way that connects the issues of young people in their everyday lives to the broader picture of a changing climate. We realised that some of the suggestions for climate action (reducing meat consumption, cycling instead of driving) seemed irrelevant to the reality of young people in marginalised communities.

So, we asked ourselves: Why isn’t climate action for everyone? How can we make the climate movement more diverse? And how do we get young people engaged in climate action?

Attempt 1

Our initial objective was to build capacity and knowledge in the youth sector.

We created session plans for youth engagement, each of which had a broad focus around climate change, environmental and climate justice. This way, we aimed to connect the issues we’ve encountered with young people to broader discussions around climate change.

We offered training and 1-2-1 support, lesson plans and funding. However, many of the presumptions about climate action were also apparent with youth workers. Many youth workers fed back that they’re overwhelmed with it, don’t know where to start, don’t know what to do and how it would land with young people. Climate change felt like a “privilege” or “add-on” topic. Something else that they were expected to address alongside all the other important things young people needed to know about.

Youth and play providers were still feeling the impact of the austerity measures imposed upon them years ago. This meant that for climate change, there was understandably a lack of interest and lack of capacity within the sector.

In addition, as the media, politicians and climate scientists tended to focus their conversation on technical data and global issues, youth workers often felt like they weren’t qualified to share their own experiences, ideas and knowledge when it came to climate change.

Attempt 2

To get youth organisations engaged in climate youth work, we realised we needed to offer a more flexible service. This allowed us tailor climate youth work to the needs of every organisation and create the most interest from young people.

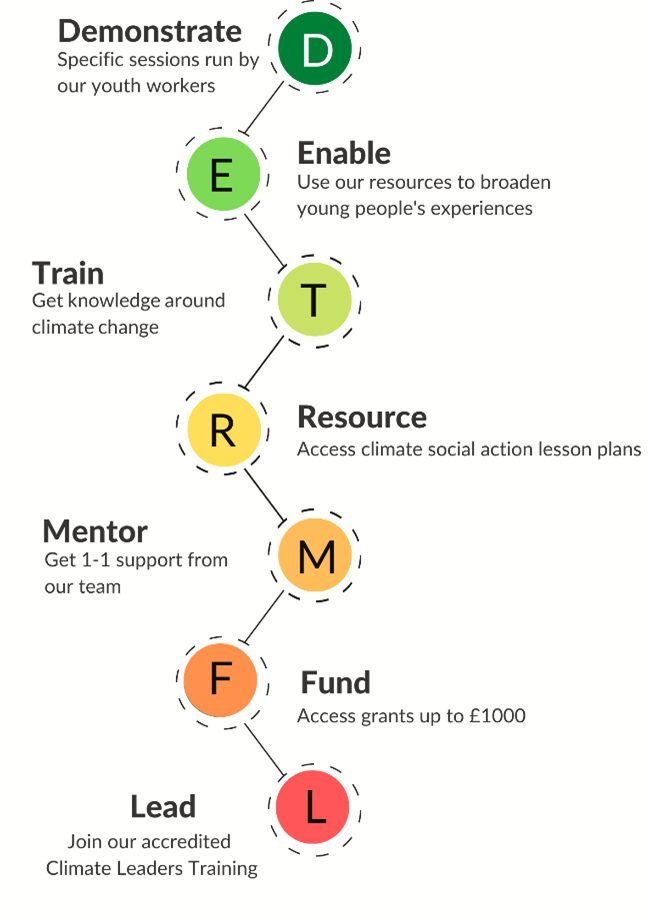

We divided our offer into 7 different modules as highlighted in the diagram.

From demonstrating youth climate work, to enabling different activities (field trip to our nature reserve), we promoted services that show and demonstrate climate youth work to youth and play providers.

Following these initial engagement sessions, we train, resource and mentor youth organisations in carrying out their own social action projects and support them with small grants.

In addition to that, we offer our accredited Climate Leaders training, so that young people who are particularly interested can access progression pathways.

This approach has been well received by various youth workers and organisations within Manchester.

Other things we’ve learnt

- Climate action is often narrowed down to a few distinct actions around changing individuals’ behaviour; eating less meat, cycling instead of driving, growing your own vegetables, recycling or participating in forms of political engagement. This approach makes out that everyday people have to solve climate change themselves, and it lets the governments, corporations and rich people who profit from climate change off the hook.

- These actions are often top-down and individualistic; substituting one consumption habit with another, more sustainable one. These actions don’t make our world fairer or less exploitative. Mostly, they just ask consumers to consume a different and more sustainable product.

- These narratives have been created by, and are mainly aimed at, a predominately white-middle class, who are more likely to have disposable income and feel guilty because of their high carbon footprints. Even the term “carbon footprint” was invented by the oil giant BP, as a way to get consumers to feel like climate change was their fault, not the fault of fossil fuel companies.

- There needs to be a sector-wide approach and levelling up of youth climate action by key commissioners and decision makers.

Huge thanks to Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester Centre for Youth Studies, Young Manchester, Manchester City Council and young people from Manchester for making this blog series possible.